RFK Jr.’s latest HHS cut is another blow to disabled and aging people

One time my mom called me by mistake and left a three-minute-long voice message, during which I could hear her calling for help again, and again, and again. It was toward the end of the two years leading up to her death, when she lived in a long-term care facility where the insufficient resources for care made her sicker and the isolation and indignity broke her heart.

The Trump administration’s move to shut down the Administration for Community Living (ACL) will most likely put many more people in the same position — ultimately costing more money and leading to worse health outcomes.

I could hear her calling for help again, and again, and again.

On March 27, the Department of Health and Human Services, helmed by Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., announced that “critical” services provided by the ACL, which works to help disabled and aging people keep living with dignity in their homes and communities rather than in institutions, will be “integrated into other HHS agencies.” The ACL’s services include oversight of state agencies and programs that protect rights and prevent abuse of older adults and those with disabilities, hotlines that help connect people with disability services and elder care and management and distribution of federal funds for services like home care, nutrition assistance, voting and employment access and caregiver support.

It’s not yet clear which of these rights and dignities HHS and the Department of Government Efficiency consider noncritical and may plan to eliminate rather than integrate. All of these services, however, are part of the ACL’s founding mission of unifying disparate programs previously administered by different agencies — in other words, creating efficiency. While no details about how or when these changes will take place were offered, layoffs affecting the ACL began immediately and will most likely continue. The entire staff of the ACL’s Center for Policy and Evaluation — which analyzed and evaluated services funded by the ACL in order to ensure, as reporting from Mother Jones pointed out, efficiency — was laid off via email. It’s unclear whether any will be rehired.

My mom’s multiple sclerosis progressed enough to make our home’s narrow halls and high mortgage unmanageable, and she entered communal living for the first time.

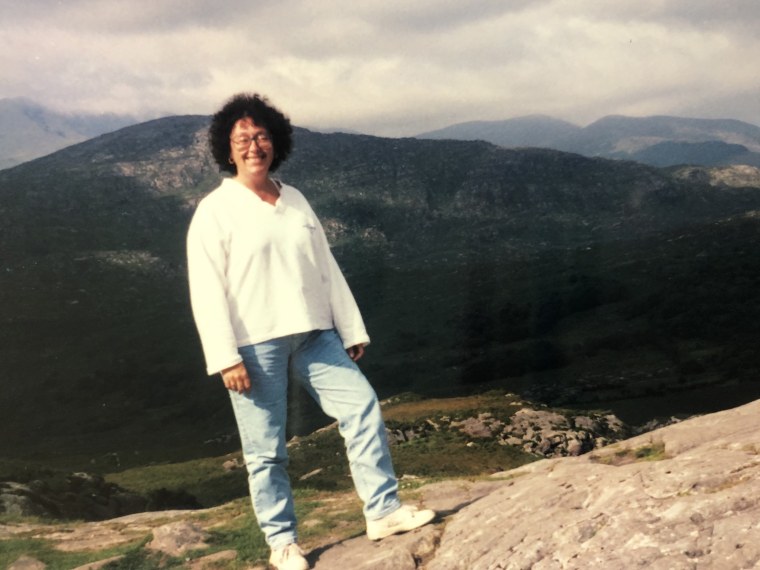

The ACL was created in 2012. Soon after, my mom’s multiple sclerosis progressed enough to make our home’s narrow halls and high mortgage unmanageable, and she entered communal living for the first time. She secured a bed in the relative freedom of a retirement community, with the understanding that she’d have preference for admission to the adjoining long-term care facility when the time came. But she was only in her mid-50s. She felt claustrophobic surrounded by people decades older than she, with the door to more intensive, restrictive care ever looming in the periphery. After a few years, despite the financial strain, she decided to move into a regular apartment. Her choice scared me, but as I entered my freshman year of college and reveled in the newfound ability to come and go as I pleased, I also understood: She wanted independence. Some programs, like the Money Follows the Person demonstration — a Medicaid program that directs federal care funding to help people transition from institutional to community living — provided assistance that made it possible for her to spend several years in her own apartment, decorated with suncatcher crystals that scattered rainbows across the trove of tacky magnets, embarrassing photos of me festooning her fridge.

But the help available just wasn’t enough. Alison Barkoff, the former acting administrator and assistant secretary for aging at the ACL, says that while the administration’s services are critical, “the funding appropriated by Congress does not come close to meeting the need.” This proved to be true in my mom’s case. Costs mounted, and she struggled to find, vet and manage scheduling for the volume of care she needed. Eventually she had a medical emergency that landed her in the ICU. After she was stabilized, the hospital declared she had to be released into skilled care. With bills mounting, she scrambled to find an open bed in an insurance-approved facility, ultimately ending up in the exact environment she had tried so hard to escape.

My mom’s experience isn’t unique. As disability activist Alice Wong has written, there are deep imperfections in how home care resources have been administered. These issues still do not deter people from preferring home and community care to institutionalization. At times, my mom suffered neglect at the hands of overwhelmed, undertrained, underpaid and occasionally unkind in-home caretakers. She also had these experiences while living in long-term care, where she had little to no control over who cared for her. On occasions when I was helping her at home, we sometimes disagreed or got frustrated with each other, like all mothers and daughters do. She still fought, at every opportunity, to live independently rather than in an institution. Wong describes how even the most frustrating experiences she has had with in-home care are preferable to living in an institution, where the same issues can play out with even less opportunity for self-determination. “Both the home care workforce and the people who need them are tired as hell and demand justice. We all deserve more.”

Dismantling the ACL will cause devastating setbacks to important work being done by organizations like the National Domestic Workers Alliance to improve conditions for caregivers and those who require care. It was community living services at their best that helped my mom achieve a level of independence and a failure to sufficiently support these services that led to her institutionalization.

This issue is particularly urgent as the U.S. population gets older on average and 1 in 4 U.S. adults live with symptoms of disability. The needs that the ACL’s services meet will not go away because the already overburdened structures designed to help meet them are demolished. Rather, they will fall to other, less prepared, already strained systems and back onto already struggling individuals and families.

“The dismantling of the administration at the same time that massive cuts to Medicaid are being debated in Congress is a double whammy,” Nicole Jorwic, chief program officer of Caring Across Generations, part of the Disability and Aging Collaborative, told me. “This change threatens to increase rates of institutionalization, homelessness and long-lasting economic hardship.”

According to a survey of care costs conducted by CareScout, a home health aide or caregiver cost an average of $6,483 a month in 2024, and a community-based day program like those supported by the ACL cost $2,167 on average. Barkoff says community living also allows people to choose when they might need help from a paid caregiver, rather than pay for 24/7 staffing in an institution. She also points out that people living in a community can access free or low-cost mainstream community resources available through institutions like community centers and places of worship. A shared room in a nursing home, by comparison, ran an average of $9,277 in 2024 and was very rarely covered by Medicare.

As the administration increasingly pushes to privatize health care, research and plenty of case studies suggest that the care nursing homes provide will deteriorate further. By contrast, older people and those with disabilities say they are happier and feel they receive better care when living in their communities. I know for a fact that my mom and I would have liked nothing more than to be able to live together.

I think all the time about the sound of my mom calling for help — and about all the times she must have called for help when I could not hear her. It’s clear Secretary Kennedy and the others gutting essential government services are not thinking about people like her at all. But when more people suffer and die sooner and more painfully than necessary because of cruel policy decisions like this, they will bear responsibility all the same.