Opinion | How Israel Divides the Right

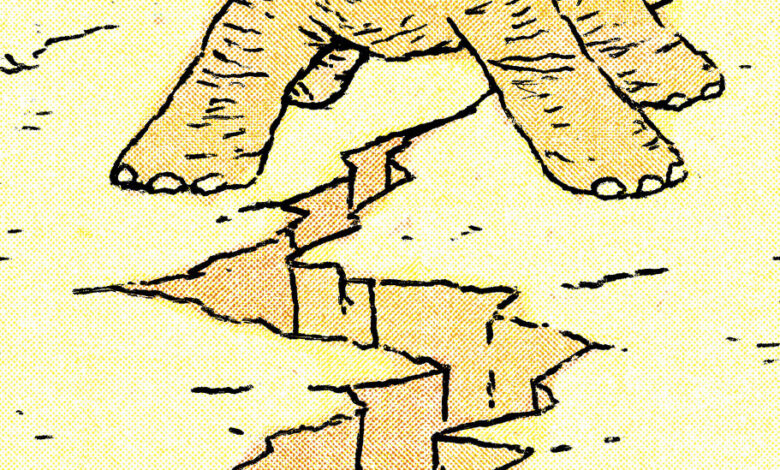

For the first year after the attacks of Oct. 7, 2023, the most profound effect in America of Israel’s war in Gaza was to destabilize the Democratic Party’s coalition. The reaction to the conflict widened an existing divide between pro-Israel Democratic Party elites and pro-Palestinian progressive activists and made unity seem impossible, leaving Kamala Harris’s presidential campaign especially stuck straddling a chasm.

In the second year of the war, the intra-liberal divides are still there, but the fractures on the right are also becoming significant. More so than in the Democratic Party, most Republican elites remain staunchly pro-Israel. But on what you might call the alienated right — younger, conspiracy-curious, anti-institutional and very online — there is a vogue for arguments about malign Jewish influences on Western politics, ranging from World War II revisionism to narratives casting Jeffrey Epstein as a cat’s paw for the Mossad.

This is not yet the kind of open, intraparty conflict that you saw in the Democratic coalition all last year — and writing for Vox, the liberal writer Zack Beauchamp suggests that it need not be, as long as the right sustains what he calls “pro-Israel antisemitism.” This is a perspective, in his telling, that divides the Jewish world into good (conservative or Israeli) Jews and bad (liberal or anti-populist or just anti-Trump) Jews and backs Israel’s right-wing government to prove its anti-antisemitic bona fides, all while maintaining a big tent for anti-Jewish dog whistles and coded bigotry — which signal to the antisemitic fringe that the right is on their side.

I think this description may capture something about the weird coalition politics in far-right European parties like the Alternative for Germany, and certainly Donald Trump divides American Jews, as he divides all groups, into good guys and bad guys, depending on whether they back or oppose him.

But where the larger Republican Party is concerned, I think Beauchamp’s framework underplays a fundamental tension: There’s just no way for mainstream Zionist Republicanism and the anti-Jewish faction on the alienated right to get along.

The most pro-Israel portions of American conservatism are not pro-Israel because of some complicated game of alliances involving support for Likud-style nationalism and opposition to Muslim immigration in Europe. They’re pro-Israel because, if they’re Christian, they’re part of a philosemitic tradition present in American life since the founding era, which intensified after World War II as both Protestants and Catholics reckoned with religious complicity in the Holocaust.

The fact that this philosemitism is sometimes encouraged by evangelical Christian subcultures that regard the state of Israel as a key player in the end times naturally makes many Jews a bit suspicious. But the philosemitism of the typical conservative American Christian is extremely in earnest: It’s not just about a tactical alliance against a liberal or progressive enemy, it’s also about a belief in a biblical mandate. And then, of course, many influential Zionist Republicans are themselves observant Jews: Ben Shapiro, to pluck just one obvious example, is not a “pro-Israel antisemite.”

Meanwhile, those parts of the alienated right that are most comfortable deploying antisemitic tropes also believe earnestly not just in some general theory of Jewish power but in a specific theory of Israel’s power, Israel’s malign influence, Israeli leaders and institutions and spies as conspiratorial and destructive forces in American life.

If you listen to someone like Ian Carroll, a popular YouTuber recently featured on Joe Rogan’s podcast, he’s not pushing a line that tries to reconcile support for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government with veiled antisemitism — something like: Oh, of course I support Israel, but you have to watch out for that conniving George Soros and the lords of international finance. To the contrary, Carroll very explicitly states that Zionism and Israeli influence are at the root of America’s problems. “Our country is controlled by an international criminal organization that grew out of the Jewish mob and now hides in modern Zionism behind cries of ‘antisemitism,’” he wrote on X last year, introducing a video titled “Evidence of a Zionist Mafia- How Israel Controls the US and Global Politics.”

That’s not any kind of “pro-Israel antisemitic” two-step. It’s just anti-Zionism and antisemitism together, the same way they show up together in parts of the progressive left. And there’s just no way to reconcile that combination with the pro-Israel politics of mainstream Republicans.

Which doesn’t mean that conservatism is going to rupture over these issues any time soon. We know that people can entertain a lot of different conspiracy theories about the world without going all in for them or making them essential to their voting behavior. We know that ideas can percolate inside an electoral coalition for a long time without becoming politically decisive — as anti-Israel sentiment that shaded into antisemitism was a real part of progressive culture for a long time without having that much impact on the Democratic Party’s elite.

And then, too, in Trump’s own approach to the Jewish state, we can see one potential Republican adaptation to having more disaffected constituents in an otherwise pro-Israel coalition. The president is transactionally pro-Israel rather than idealistically Zionist; he’s more willing to put pressure on Israeli leaders than a different Republican might be, and for those members of his coalition who are open to critiques of Israeli policy without going all the way to Ian Carroll territory, that posture might be satisfying enough.

For now. But events matter, too — not just the war in Gaza and its effect on Western culture wars, but also the direction and endgame of the Trump administration.

That’s because populism by its nature always carries a somewhat conspiratorial view of the world — a belief in a network of elites, powerful and insulated and incestuous, who have failed their country and need to be defeated and replaced.

A belief can be conspiratorial without being false: Our elites are incestuous and insulated; they have failed in important ways.

But the intensity of the belief primes populists to always blame their own struggles on the hidden hand, the inner ring, the “deep state.” And if the real-world “deep state” seems to have been rendered mostly impotent, if the bureaucratic forces that resisted Donald Trump in his first term seem weakened or defeated and yet things still don’t go the way populists would hope — if there’s an economic crash or a foreign policy fiasco — well, then, you need a different story to explain what happened.

For many populists, that will just mean discovering new enemies in the ranks of insufficiently pro-Trump conservatives. But for the most alienated Americans, the antisemitic story will be there waiting, the way it always waits — offering to the baffled and unhappy a scapegoat of last resort.

Breviary

Kevin Roose expects the A.I. revolution.

Thane Ruthenis makes the bear case.

What did the Brothers Grimm achieve?