Opinion | Bernie Sanders, A.O.C. and the Surging Politics of Anger

They gathered early in North Las Vegas, waiting under the hot sun in a snaking line in the middle of a workday for their chance to see Senator Bernie Sanders.

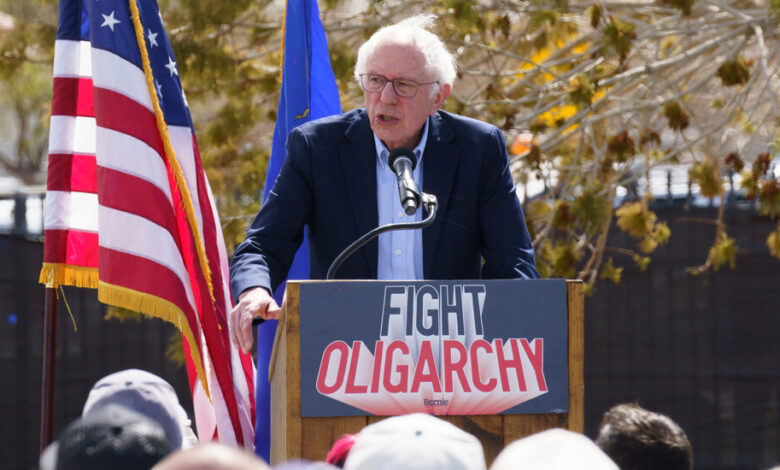

With stucco houses and apartment blocks interrupted by strip malls and trash-strewn vacant lots, this is not the Vegas you see in glamorous movies. It was, however, the setting for what Mr. Sanders, independent of Vermont, called the biggest crowd he had ever drawn here. Nevada was the first Southwestern stop for Mr. Sanders, who, along with Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, had set out on what the pair called the Fighting Oligarchy tour.

Packing venues all over the country — in Nebraska, Iowa, Arizona and Colorado — Mr. Sanders appears more popular than ever. His core message hasn’t changed in decades, but it’s hitting harder now. In hours of interviews with all kinds of people at the Nevada rally on Thursday, two unbroken trends emerged: Everyone I met was having money problems. And all of them were frightened, some for the first time, that the country they’d always counted on was sliding away because of President Trump.

If these conversations are any measure, many Americans are reaching a breaking point. Already struggling to make ends meet, people are wondering how much leaner things could get if a recession hits. They see Mr. Trump defy the Constitution and ravage parts of the federal government that have long seemed as unremarkable and permanent as boulders — and they fear that, before all is said and done, he’ll come for Medicaid, public schools, veterans’ services and Social Security, too. Maybe take our freedom of speech, while he’s at it.

It was all there at the Sanders rally: dread, yes, but also an anger and an appetite — a tremendous, largely untapped political energy looking, it seemed, for an outlet.

“I just got the worst of fears,” a recently retired sheet metal worker named Kelly Press told me. “You get up in the morning, you don’t know what you’re going to go to bed losing.”

Mr. Press, a strapping 65-year-old from Detroit who spent his working years bouncing around construction sites in the West, wore a cap from his union (Sheet Metal Workers Local 88), a chunky ring on each hand and dark glasses shading his blue eyes. Moving to Vegas inspired him, at one point, to work as a craps dealer, which gave him a lingering aversion to the cruelties of gambling and sent him scuttling back to the comparatively placid world of construction sites.

If someone got on the stage that very day, he said, and asked the crowd to march all the way to Washington to protest against Mr. Trump, Mr. Press would take that long walk without hesitation — “I swear to God.”

“But there’s nobody like that,” he said. “There’s nobody giving anybody any kind of direction. I think everybody is really scared and lost.”

When he retired two years ago, Mr. Press calculated that he could get by on $1,000 a month for gas and food. And for a while, he could — but prices have crept steadily higher, and his monthly bare minimum has ballooned to $1,400. He understands, in a way, why some of his union friends went for Mr. Trump — Mr. Press said they were tired of paying taxes and union dues and protective of their guns — but he believes they made a grave mistake.

“I can see this whole country being like Russia,” he said. “Where you can’t even speak about elected officials.”

The hunger Mr. Press described — for somebody to stand up to a White House that is flouting judges’ rulings, threatening public services and scoffing at civil liberties — was pervasive in the crowd.

While Democrats agonize over losing the working-class vote, visiting podcasts and TV studios to strategize how to get it back, only Mr. Sanders seems to understand how to tap into the dissatisfaction of the crowds.

Which is interesting, because he’s not really saying anything new. Mr. Sanders’s rally speeches offer the same program he’s been advocating, often for decades: Medicare for all, lowering prescription drug prices, taxing the wealthy, free state college, strong unions, raising the minimum wage. If you follow him, you’ve heard it before.

One could hardly accuse the willful Mr. Sanders of adapting himself to the moment; it’s more accurate to say that the moment has adapted itself to him. Now that his most dire warnings have manifested themselves, gradually and then with sickening speed, he looks, at once, prescient and thoroughly relevant.

Now he can tie it all together — the privations people are enduring, the unease they’re feeling and his long-unheeded arguments. Soaring prices, he preaches, are down to the concentration of corporate ownership. Mr. Trump’s autocratic tendencies and emerging oligarchy — personified by Elon Musk, the world’s richest person — are evidence of the senator’s longstanding insistence that staggering wealth inequality will be our collective undoing. He connects Mr. Trump’s attacks on federal bureaucracy to the household budget problems of people clapping along in the crowd. They’re not just arbitrarily dismantling the government, he explains; they’re doing it so they can give themselves a trillion-dollar tax break.

In North Las Vegas, tightly packed under the blue shellac of a desert sky, the audience periodically broke into hearty chants of “Tax the rich.” Music piped through the park: “Everybody wants to rule the world.”

Ms. Ocasio-Cortez warmed up the crowd. She hit out at her own party (“We need a Democratic Party that fights harder for us,” she cried out to enthusiastic cheers) and called for everyone from Trump voters to families of trans kids to come together and organize locally.

“This movement is not about partisan labels or purity tests,” she said. “It’s about class solidarity. The thousands of people who came out here today to stand here together and say, ‘Our lives deserve dignity, and our work deserves respect.’”

And then, to the roar of his name, Mr. Sanders appeared. He thundered against Mr. Trump. He took aim at the tech bros, pointing out that the three richest Americans — Mr. Musk, Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg — own more wealth than the 170 million people who comprise the bottom half of American society. He derided the predatory behavior of a tiny, uber-rich ruling class that he described as frivolously self-indulgent and cloistered from economic realities.

“They have no clue what is going on in the real world,” he shouted.

This, Mr. Sanders likes to remind Americans, is the richest country on the planet.

“No, we will not accept an oligarchic form of society where a handful of billionaires run the government,” he exhorted the crowd.

He railed against Mr. Trump’s attacks on the Constitution and then pivoted to ask the crowd, “What does it mean to live paycheck to paycheck?”

People shouted back, and Mr. Sanders repeated their words into the microphone:

“How to put one’s kids through college.”

“Whether or not you’re going to buy your prescription drugs or pay your rent.”

“Knowing how to pay your credit card when interest rates are 20 percent.”

At that point, a young woman standing near me shot a significant look at the man at her side and muttered, “Twenty percent would be nice.”

Mr. Sanders took it all in, then informed the attendees that their life expectancy is lower than it is for those in other comparable nations and, even worse, that the life expectancy for lower-class Americans is significantly shorter than for their wealthier compatriots.

The message landed. The crowd hung on his words, pumping fists in the air, booing noisily or raising middle fingers when he mentioned Mr. Trump or Mr. Musk. There was a sense of catharsis.

“He brings awareness of what’s going on in the country, and he’s giving voice to those who are voiceless,” a second-grade teacher named Dina Garibay told me. “He wants to stand up for the rights of everybody, and the Democratic Party doesn’t always stand up for that.”

Ms. Garibay, 56, comes from a heterodox political background. She was a Reagan-era Republican who soured on the G.O.P. because she felt it coddled the wealthy. She then gravitated toward the Democrats but has been frequently disappointed there, too. If she voted solely on platform, she said, she’d probably go for the Green Party, but that would be a waste of a vote, because it can’t win.

Under the circumstances, though, she just wants somebody to do something.

“It feels like the rug is being pulled out from under us,” she said.

Ms. Garibay was appalled by Mr. Trump’s efforts to close the Department of Education, which she anticipated would hurt children who have special needs. She’s Latina and was incensed by his talk of mass deportation. She was worried about the rights of the L.G.B.T.Q. people, among whom she counts herself.

At the same time, she is mired in Las Vegas’s affordable-housing crisis, which is one of the most acute in the country. Ms. Garibay moved here a few years ago from Arizona, hoping to buy a house. After a humbling search, she realized that ownership was unambiguously beyond her financial means. She lives with her husband and teenage daughter in a mobile home on a rented plot, pinching pennies as the family’s weekly grocery bill has climbed from around $120 to $200. Some of her colleagues, she said, drive for Uber in the evenings to supplement their salaries.

“Every single teacher I know can’t afford a home,” she told me. “We work very, very hard for our money, and we see it just going into rentals.”

All of that and more — “How long you got?” was a refrain I heard repeatedly when I asked people why they had come — brought her out to cheer for Mr. Sanders.

No need, anymore, for Mr. Sanders to try to get Americans to imagine dark lounges where corporate lobbyists pad the pockets of politicians in exchange for compliance. Mr. Trump has brought it all into plain sight. Mr. Musk’s more than $270 million in campaign spending bought the top job in Mr. Trump’s administration, where the eccentric tycoon who dreams of sending humans to Mars now enjoys a free hand to tamper with federal programs that form an already tattered safety net for elderly people, veterans and poor Americans.

“There’s almost nobody in America who thinks that it is not insane,” Mr. Sanders told me backstage at the rally.

All of that makes it easy for him to fuse his leftist economic analysis to the animating fears of more centrist Democrats, who have been talking about Mr. Trump as an authoritarian spoiler all along. Mr. Sanders can also beckon to working-class swing voters who’d hoped Mr. Trump would at least bring down prices.

Even amid his tirades against Mr. Trump, Mr. Sanders saves some blows for Democrats. He credited the party for advancing civil rights and protecting women and L.G.B.T.Q. people but added that Democrats had, meanwhile, neglected the basic needs of lower- and middle-class Americans.

“I think one of the reasons Trump is doing so well with working people — it’s not because they think we should give tax breaks to billionaires,” he told me. “They’re responding to Trump because Democrats have kind of abdicated the area.”

Mr. Sanders, who pointedly reminded me that he is the longest-serving independent in the history of Congress, argues that the Democratic Party should either change to meet the moment (“We’ll see if that’s possible or not”) or prepare to be abandoned.

“My hope is that the Democrats can regain the kind of worldview that they had in the ’30s and ’40s under Roosevelt and Truman and become less dependent on corporate interests,” he said. “And if that doesn’t happen, I would hope that people would decide to run as progressive independents, working with Democrats when they can.”

Back in the crowd, I met Sam Laurel, a 33-year-old pool cleaner who’d donned his “Eat the rich” T-shirt for the occasion. He wanted to be part of the crowd, he said, to show “how much we’ve had it with our government bending over for the 1 percent and not doing anything for us.”

Like Mr. Sanders, Mr. Laurel talked about politics in a cascade of Mr. Trump’s misdeeds and his own tribulations: He lives with his parents. None of them can afford to live separately. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which Mr. Laurel called “the anti-scam police,” has been kneecapped. He finally has a job with health insurance after years of doing without, and he blamed the stress of those years for the premature silvering of his hair. Mr. Trump is going to attack Social Security and Medicare. Mr. Laurel would like to go to college and become a teacher, but he didn’t know how to pay for it.

“The government should work for us, the many,” he said. “We’ve all just had enough of being sucked dry.”

He spends his days cleaning the tranquil garden retreats of wealthy clients, which brings the problem of economic inequality into sharp and sometimes unwelcome relief. In Las Vegas, a town full of glitter but grounded in dust, he works to keep other people’s chemical waters crystalline, and the Sanders-tinged ruminations about working-class struggles and the mirage of luck can look especially stark. One of his clients is a celebrity who lives elsewhere and just can’t get around to fixing a badly leaking pool. “Draining Lake Mead,” Mr. Laurel mused, shaking his head.

“I like to be alone with my thoughts,” he added. “But I’m alone with my thoughts in rich people’s backyards.”