Does your natural history museum need a makeover?

At first glance, it’s a simple scene. Six adult bison and a calf mill around a stream. But if you look closer, the plot thickens.

Beside a well-worn path to the stream sits a bison skull. This herd has clearly been dropping by for some time. And they’re playing a key role in the ecosystem. Scattered birds feast on bugs kicked up by the bison.

Peer into the trees on the scene’s far right, and you might even spot what only one bison has noticed. Two wolves lurk, eyeing their next meal.

“Dioramas, they have such rich stories,” says Matt Davis. He develops exhibits in California at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles. That’s where this bison diorama is displayed.

Imagine, Davis says, seeing this scene when the museum’s first diorama hall opened in 1925. TV didn’t exist yet. Full-color movies were still brand new. For many city dwellers, dioramas were the only way to see animals as they might live.

It might be like an extreme virtual-reality experience today, Davis says. “People were totally blown away.”

If you’ve ever been to a natural history museum, you’ve likely seen the diorama hall. These big rooms often feature groups of animals. Some display models of people, staged in lifelike poses against painted backdrops. In fact, it might be hard to picture a museum without them.

But these exhibits have a complex and often troubling history. Diorama builders have historically gotten their materials by taking advantage of the places the animals come from. And some designers created displays that, to modern eyes, are inaccurate or offensive. Plus, some museum visitors today simply find dioramas dull or even creepy.

This “diorama dilemma” is forcing modern museums to reconsider how they present exhibit such scenes. Some museums have reduced or removed them. Other curators and artists are playing with new diorama formats. Still others are reframing old dioramas to address misleading or racist depictions.

What this means: Diorama halls of the future might look a bit different from those you grew up with.

This revamp “needs to happen,” says Aaron Smith. He’s director of exhibits at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco.

The new age of museum makeovers doesn’t spell an end for dioramas. For decades, these displays have evoked a sense of “awe and wonder,” Smith says. “That still exists.”

Dioramas’ troubled history

It’s hard to pinpoint the very first dioramas. Charles Willson Peale made one of the earliest in the 1780s. Peale practiced taxidermy. That’s the craft of stuffing dead animals to preserve them with a lifelike appearance.

At his own home, Peale set up a mound of earth covered with turf and trees, plus a fake pond. There, he placed taxidermied birds, snakes, a tiger and other specimens.

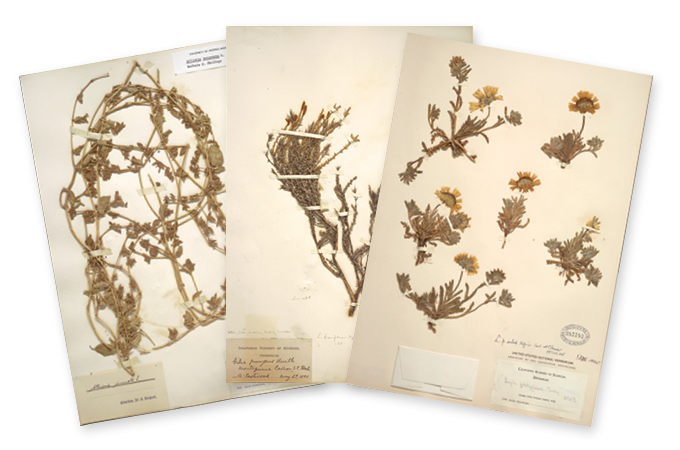

By the early 1900s, natural history museums started making habitat exhibits like this. These dioramas were often created by taxidermists who led hunting trips to shoot the most spectacular specimens — including endangered animals.

Hunters saw their work as one way to preserve the last of disappearing species. They also hoped these dioramas would inspire viewers to conserve the animals that remained in the wild. But they were killing endangered animals to do this. And in many cases, the hunting trips offered an excuse for rich, white men to get out their guns and kill big game for sport.

“A lot of this was boys with their toys,” says Marjorie Schwarzer. She wrote the book Riches, Rivals and Radicals: A History of Museums in the United States.

Sometimes hunters recognized the conflict between their hunting trips and the goal of conserving species. Carl Akeley was one example.

He shot mountain gorillas in what was then the Belgian Congo. The experience changed him. He persuaded the king of Belgium to set up Africa’s first wildlife sanctuary. Today, it’s called Virunga National Park. It’s home to some 350 endangered mountain gorillas in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Diorama-maker William Temple Hornaday also had a change of heart. He went to Montana in 1886 to collect bison for the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. On that trip, he was shocked by how fast the bison population was shrinking. So he brought live animals back to D.C. In 1889, they became the first animals in what would become its National Zoo.

Are dioramas worth saving?

A century later, museums were starting to wonder if dioramas still had value. Many were unscientific. For instance, they tended to overuse large male animals and overlook females. Dioramas also had to compete with new multimedia exhibits.

In the early 2000s, some museums scrapped or cut back on dioramas. Others tried to modernize them with interactive parts and animatronics. But those choices weren’t always rooted in any science on the value of dioramas.

The Oakland Museum of California took a different approach. It asked Schwarzer and a curator to study people’s reactions to dioramas. The pair looked at 30 studies of more than 3,800 people viewing dioramas at 17 institutions.

In 2009, the researchers came up with a strong case for dioramas. It turns out that the displays are second only to dinosaurs in getting visitors to stop and look.

Dioramas didn’t change how people felt about conservation, the study found. But they did reinforce concerns people already had about the environment. They also sparked a range of emotions. Some viewers felt creeped out by dead animals. But most people loved these exhibits.

Museum staff see similar responses today. “I do walk-throughs all the time of the museum, and I can hear the ‘Whooooaaaa!’ ” says Mariana Di Giacomo. She’s a natural-history conservator at the Yale Peabody Museum in New Haven, Conn. The Peabody’s oldest and largest dioramas show Connecticut’s coastal region and a forest edge.

Chicago’s Field Museum recently got public support to finish a diorama started more than a century ago. Akeley had mounted four striped hyenas shot in 1896. But they never got the full scenic treatment. In 2015, the museum launched a social-media campaign to finish the project. In just six weeks, some 1,500 donors raised more than $150,000.

Gretchen Baker led planning for the museum’s exhibits at the time. “It showed us that there is an enduring interest in these dioramas,” she says.

Battling biases

Dioramas’ eye-catching nature gives them great storytelling potential. Unfortunately, the stories many tell are not entirely scientific.

“A lot of people have called them, in the past, ‘bad science’ because they personify animals,” Schwarzer says. Many dioramas, for example, show animal groups that include a mom, dad and babies. But many species don’t live that way. Papa bear does not stick around to help raise the cubs. Indeed, Schwarzer says, “Papa bear might eat a couple of the cubbies.”

Some exhibits misrepresent female animals, too, Baker notes. She now directs the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pa. One diorama there shows a female moose standing in water. This makes her look shorter than the male on land.

Females are often the ones who lead animal groups in the wild. But Baker observes that they don’t usually take charge in dioramas. Likewise, homosexuality exists in nature but rarely shows up in dioramas.

In many cases, designers likely wanted to show the different forms of the animals, says Mark Alvey. He works at Chicago’s Field Museum. Mom-dad-baby groups offer an easy way to show adult males, adult females and young all at once.

“We always knew it was wrong,” Davis says. “Now, we’re slowly trying to fix some of those things.” For example, the L.A. museum has added more females to its lion pride.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

The human element

There also are problems in how people are — or aren’t — depicted in dioramas.

Some ignore humans completely. This erases the long-term presence of Indigenous peoples in many places. It also ignores the impacts of modern societies on the environment. And that’s misleading. Today, very little of the world is untouched by humans.

“The kind of nature that dioramas exhibit, it’s very unnatural,” says Martha Marandino. A professor of biology education, she works at the University of São Paulo in Brazil.

New York’s American Museum of Natural History recently dealt with problems in its “Old New York” display. Made in 1939, it shows a fictitious 1660 meeting between a Dutch leader and high-ranking members of the Lenape Tribe. The Lenape people were the original residents of the land that would become Manhattan.

Stereotypes riddle the display. Only Lenape men are in on the discussion. And they wear loincloths. That’s not how they would have dressed for a diplomatic meeting. Plus, only the Dutch leader, Peter Stuyvesant, was named in the original display.

In 2018, curators added labels to explain problems with this display. They also added the name of the Lenape leader Oratamin.

Sometimes, this type of reframing isn’t enough to fix a diorama’s problems.

Take “Lion Attacking a Dromedary.” (A dromedary is a type of camel.) This display, created in 1867, showed a dark-skinned man on camelback under attack by lions. One lion was male, even though it’s generally females who hunt. Worse, the man was dressed in a mishmash of clothes that represented no specific culture. To top it all off, the mannikin head held a real human skull.

The whole display had been created by known grave robbers.

“It’s not educating anyone on anything that ever existed,” points out Aja Lans. She’s an archaeologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Md.

Andrew Carnegie bought the diorama in 1899 for his museum in Pittsburgh. In recent years, staff have tried putting up warning signs, so people could avoid the diorama. They also added labels to point out its problems.

Then, in 2020, a white police officer murdered a Black man, George Floyd, and sparked a nationwide conversation about racism.

“This diorama was kind of like a poster child for all of these questions that were coming up,” Baker says. “It was kind of this symbol of a time in natural history museums when we would display the other — the exotic — the colonized.” That summer, the museum covered the display completely.

In 2023, the museum chose to no longer display human remains at all. So it shut down this diorama for good. It’s now being taken apart. Lans and colleagues are analyzing bits of teeth from the skull to pin down its origins. The museum hopes to return it to the country where the man grew up.

Dioramas for a new age

Back in Los Angeles, upstairs from the bison is a revamped diorama hall. It shows some drastically different scenes.

One, called “Special Species,” pulses with changing lighting and bright colors. It’s home to piñata-style sculptures of at-risk California critters. There’s the Chinook salmon, for example, and the desert tortoise. The sculptures are in the style of fantastical Mexican creatures called alebrijes. (You might have seen some animals like these in the film Coco.)

Artist Jason Chang, who goes by RFX1, was on the team that created the diorama. He hopes viewers will walk away with “an urgency to protect the environment.”

“Special Species” is just one part of the exhibit “Reframing Dioramas: The Art of Preserving Wilderness.” This project highlights dioramas’ historical importance while adding modern science. “It’s a hall on dioramas, not a hall of dioramas,” Davis explains.

In one new diorama, video projections show how the Los Angeles River has changed over the centuries. Another shows an eerie scene in which wildebeest sip from a polluted stream amid metal-plated plants.

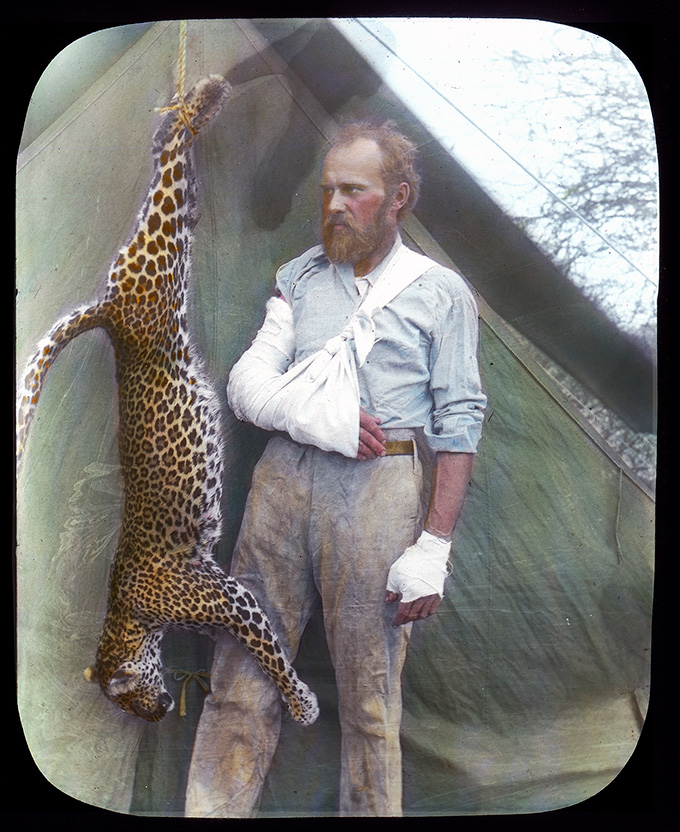

Still other displays show how traditional dioramas came to be. One shows a partially constructed diorama, still in pieces. Another features a hunting camp-style tent. That exhibit calls out the power imbalances at work when rich, white hunters traveled to extract specimens. Today, that display notes, most large specimens that the museum mounts died of natural causes. (They come mainly from zoos or wildlife centers.)

For all their problems, wildlife dioramas still serve their intended purpose. They bring striking nature scenes to people who might never see them in the wild. They also retain their power to inspire wonder and a love of nature.

The science and art of dioramas will continue to evolve. Davis hopes the L.A. museum’s new exhibit lights the way.

“We don’t think this will be the last word on dioramas,” he says. “We hope it’s the first word.”