Denzel Washington in ‘Othello’: Theater Review

If there is an American leading man better-equipped to bring Shakespeare to the masses than Denzel Washington, I can’t think of him.

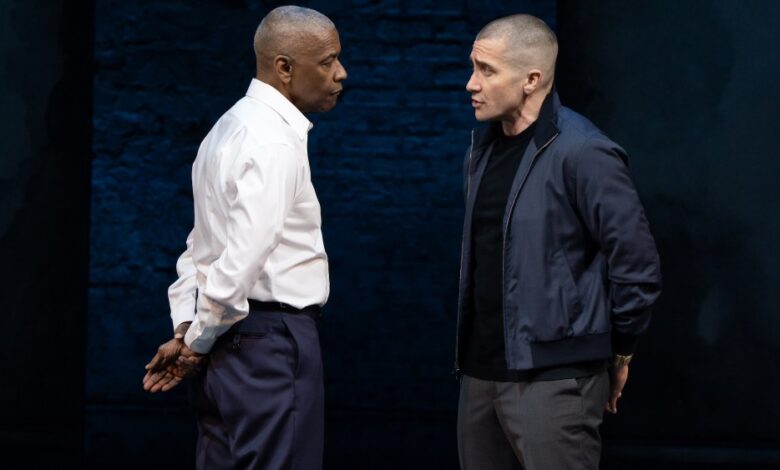

Well, “the masses” may be a stretch — the new production of “Othello” that Washington leads, now playing at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre, has broken box office records on the strength of orchestra tickets selling for over $900 a seat. That lucky group of people who will get to see this “Othello” will get to luxuriate in Washington’s silky, fluent delivery of the Bard’s English, and to thrill to the painful irony of Othello’s fundamental lack of understanding that he’s being played by the jealous, venal Iago (an excellent Jake Gyllenhaal).

But that’s about all they’ll get. Clumsily staged by director Kenny Leon, this “Othello” seems to have little on its mind beyond a gritted-teeth determination to carry across the text of the play. “Othello” is “Othello” — one of the richest and most wrenching of Shakespeare’s tragedies. It would take a wildly misbegotten production to spoil it entirely. But that hypothetical wildly misbegotten production might contain some genuinely big risks; this production, instead, simply falls flat.

Washington, here, is the title character, a military general whose personnel choices have enraged Gyllenhaal’s scheming underling. The great tragedy of Othello, perhaps, is how easily he allows his misplaced trust in Iago to lead him astray; the villain’s well-chosen lie wrenches apart Othello’s marriage to Desdemona (Molly Osborne). The simple, brutal brilliance of Iago’s scheme is the way that it takes advantage of a certain intractable reality. Othello, for all his brilliance, is the Other — a man of color among white Venetians — and exists within a certain matrix of barely-concealed mistrust.

All of which would seem to provide Washington and Gyllenhaal plenty with which to work. And, indeed, this “Othello,” we’re informed by a projected legend as the show begins, transpires in “the near future.” Its characters alternate between business-casual (Washington enters tucking a dress shirt into slacks) and contemporary military fatigues. Transposing Shakespeare to something like the present day is hardly novel (it happened earlier this season in director Sam Gold’s “Romeo + Juliet,” for instance), but, when done well, it extracts some crucial insight about the unchangingness of human nature.

Instead, “Othello’s” setting now seems effectively random, less a choice than the refusal to make a choice. (That’s not a problem faced by Gyllenhaal, at least, whose alternation between ingratiating suavity and darting, weaselly insecurity turn his Iago into an utterly modern figure — his words may be Elizabethan, but his bearing is that of a men’s rights activist.) The recent film “Gladiator II” made clear that period trappings don’t overwhelm Washington; indeed, in that potboiler, old-timey raiments enhanced his bearing. His nondescript outfitting here, though, diminishes him; his Othello, lacking a certain verve from the first, seems in a sense defeated even as, early on, he is riding high, making his eventual collapse feel a touch too inevitable.

If this production must be set (sigh) in the near future, why not add touches to the staging that make clear we’re one step closer to dystopia? Instead, the stage is dominated by columns with a terra cotta effect, but little else; the world Othello and Iago inhabits seems less drained of color than awaiting it, as if Leon forgot to put it there in the first place. Other choices seem so misjudged as to be outright bizarre: Gyllenhaal’s several monologues to the audience confessing his desire to sabotage Othello take place under an obliterating spotlight, while one crucial scene of violence takes place in darkness and behind a pillar. In both cases, the lighting works to conceal the story, without adding new meaning.

Amidst this drab landscape, both actors do their best. I referred earlier to Washington’s excellence with line delivery advisedly: He is made, late in the show, to feign a seizure in a moment that doesn’t land, and the blocking of his final scene, in which the actor mutters to the ceiling while lying on his back, similarly thuds. When upright and addressing the countrymen he is among but not truly of, he has that familiar brash energy, as if attempting through sheer force of will to move past the fact that he is of another race than all of his peers. And Washington’s initial chemistry with Osborne, playing his wife, is strong enough, despite a striking difference in age, that their later scenes coruscate with a painful sense of betrayal. Indeed, these scenes capitalize on all 70 of Washington’s years on this Earth, as he looms over Desdemona and speaks with an authority his misguided beliefs have not earned.

That Washingtonian authority demonstrates the production’s one big idea — to place two big stars at the center of the stage and trust that their talent and charisma will carry the day. And, for the most part, they do; no fan of Washington or of Gyllenhaal will leave disappointed in the actors. Leon lets his two stars cook, but hasn’t stocked the production with anything to give what they’re doing any flavor.