Researchers discover 132-year-old Great Lakes shipwreck, fate of Gilded Age titan

It was a real deep mystery.

Researchers have finally discovered the final resting spot of the historic Gilded Age ship Western Reserve — closing the book on a caper that has endured for over a century.

The historic steamer had reportedly disappeared during a summer cruise in Lake Superior in 1892, resulting in the deaths of owner and millionaire shipping titan Peter G. Minch, his young family, and all but one of the 27 passengers aboard, USA Today reported.

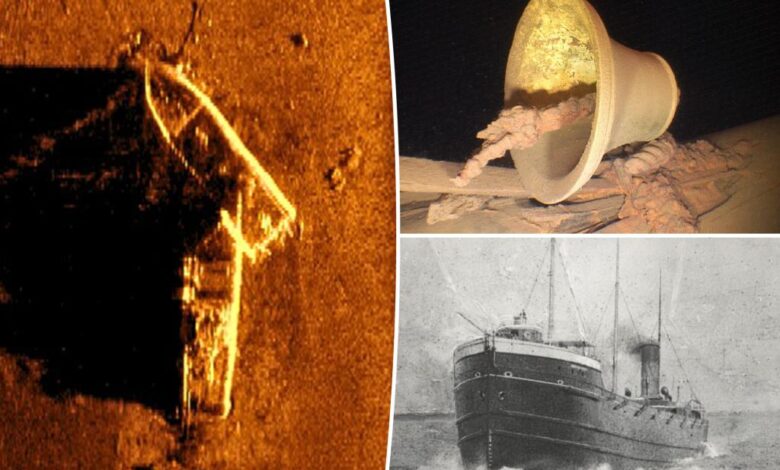

This freighter lay undiscovered for 132 years until this past summer when a team with the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society discovered the wreckage 600 feet down off the coast of Michigan’s upper peninsula. They revealed its final resting place Monday at the Wisconsin Underwater Archeological Association’s annual Ghost Ships in Manitowoc.

“The final resting place of the 300’ steel steamer Western Reserve has been discovered roughly 60 miles northwest of Whitefish Point in Lake Superior,” the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum said in a March 10 news release, per the Sun Herald.

Much like the Titanic would be years later — in more ways than one — the Western Reserve was an iconic vessel in the late 19th century. Dubbed the “Inland Greyhound” for its speed, the trailblazing freighter was the first ship built for the Great Lakes that was comprised entirely of steel.

At 300 feet long, this marvel of modern engineering wasn’t a mere ship — it was a symbol of the unbound optimism of the Gilded Age that was built to “break cargo records,” the Daily Mail reported.

In August 1892, owner Captain Peter G. Minch and his family embarked on a summer pleasure cruise aboard the vessel — which was also deemed the “safest ship in the world” — with plans to travel up through Lake Huron and onto Minnesota.

“It is hard to imagine that Peter Minch would have foreseen any trouble when he invited his wife, two young children and sister-in-law with her daughter aboard the Western Reserve for a summer cruise up the lakes,” said Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society Executive Director Bruce Lynn. “It just reinforces how dangerous the Great Lakes can be any time of year.”

Indeed, the fateful voyage was apparently going swimmingly until the evening of August 30, when the winds began to pick up after the crew arrived in Lake Superior’s Whitefish Bay.

The gales were so powerful that the nautical juggernaut’s seemingly indestructible steel frame began to break apart.

The Western Reserve’s fate seemed sealed — some 60 miles from the shore.

Left with no other recourse, all 27 passengers desperately piled into two lifeboats — one wood and one steel — but to no avail. The metal vessel overturned immediately, causing its occupants to drown in the raging lake.

Meanwhile, the wooden lifeboat, which was boarded by Minch and his family along with wheelsman Harry W. Stewart and another crewmember, drifted for ten hours before capsizing a mile from shore. Stewart was the only one to make it to land, whereupon he relayed the tragic saga.

“If it wasn’t for Harry Stewart, we really wouldn’t know what we know today about the Western Reserve,” said Lynn.

The shipwreck’s location remained a mystery until summer 2024 when, after an exhaustive two-year search, GLSHS Director of Marine Operations Darryl Ertel and his brother Dan happened across the sunken vessel’s gravesite.

They reportedly picked up a peculiar shadow on their Marine Sonic Technology side-scan sonar aboard their research vessel David Boyd.

“We side-scan looking out a half mile per side and caught an image on our port side,” Darryl told the outlet. “It was very small, looking out that far, but I measured the shadow, and it came up about 40 feet.”

He added, “So we went back over the top of the ship and saw that it had cargo hatches, and it looked like it was broken in two — one half on top of the other.”

Darryl realized that they were “right on the money” after discovering that halves each measured 150 feet — half the length of the Western Reserve.

Their find was confirmed by two remote-controlled submersibles that descended into the depths to reveal the fragmented remains of the fallen freighter.

“Knowing how the 300-foot Western Reserve was caught in a storm this far from shore made an uneasy feeling in the back of my neck,” Darryl said while reflecting on the momentous find. “A squall can come up unexpectedly… anywhere, and anytime.”

For Lynn, the catastrophe illustrated the dangers of the Great Lakes, which are home to some 6,000 shipwrecks in which 30,000 people have died.

“Every shipwreck has its own story, but some are just that much more tragic,” he said.