The einstein tile rocked mathematics. Meet its molecular cousin

For centuries, mathematicians and floor designers alike have been fascinated by the shapes that can tile a plane — in particular, those that do so without repetition.

Now, a team of chemists has described a molecule that naturally assembles into these irregular patterns, laying the groundwork for engineering materials that behave differently from regular solids.

“When these things seem to arise spontaneously in nature, I think it’s absolutely fascinating,” says Craig Kaplan, a mathematician and computer scientist at the University of Waterloo in Canada who was not involved in the study. “It feels like you found a glitch in the matrix.”

In 2018, chemist Karl-Heinz Ernst and colleagues were spraying a special hydrocarbon molecule onto a silver substrate and watching it form patterns through a microscope.

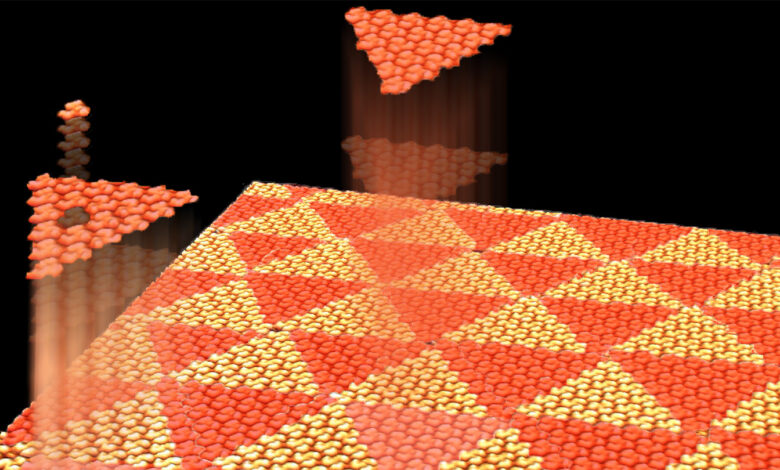

“We saw something that was quite surprising and amazing,” says Ernst, of the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology in Dübendorf. The deposited molecules formed three-armed spirals, which grouped together into triangles of slightly different sizes. In each of around 100 experiments, the researchers found new triangular sequences that never seemed to repeat. They sat on these images for years trying to make sense of them.

Then, in 2023, Kaplan and collaborators stunned the mathematics world when they found the elusive einstein tile — a single shape that can fill a floor only with a never-repeating pattern, meaning it’s aperiodic. The mathematical discovery helped Ernst and colleagues put the pieces together: It seemed as though they’d stumbled upon a sort of molecular einstein.

Kaplan cautions that the patterns in this material aren’t aperiodic in the same sense as the einstein tile. The pieces don’t fit together precisely, and it’s unlikely — if not impossible — that they can tile only with nonrepeating patterns. But even without achieving true aperiodicity, the novel patterning may be sufficient to grant the material some seemingly magical properties, Kaplan says.

Physicists have known for decades that electrons behave differently in quasicrystals, materials whose atomic structure exhibits some large-scale order but lacks repeated patterns. Last year, physicist Felix Flicker at the University of Bristol in England helped build a computer simulation of a quasicrystal based on Kaplan’s einstein tile, which predicted it would act like a tricked-out sheet of graphene.

How quasicrystals form in nature remains a big mystery, Flicker says. The spirals Ernst grew may provide some clues.

The key to this molecule’s irregular behavior, reported in January 2025 in Nature Communications, may be the entropy of its constellations.

Entropy is a measure of how disordered a material is, or alternatively, how statistically probable its atomic arrangement is. The molecule has two tricks that make it abnormally versatile: It can easily convert between two distinct mirror-image shapes, and it forms very weak intermolecular bonds, allowing it to switch between large-scale configurations relatively easily. These two properties together mean that there are many possible ways for the molecules to arrange without repeating, Ernst says. The molecules thus flock to higher-entropy, nonrepeating patterns — ordering in the most disorderly way possible.

Flicker says the new study provides “a really nice example of this ‘order by disorder’” theory of quasicrystal formation. Understanding the general principles of irregular ordering could point scientists toward better ways to engineer quasicrystals on demand. Flicker believes that uncovering new patterns that lie between regularity and randomness is bound to yield exciting connections in unexpected places.

Ernst is humbled by the fact that the molecules found these patterns all on their own. “This is nature doing math,” he says.